ZLW History

SOME OF THE HISTORY OF ZLW WELLINGTON RADIO

Most of the material for this section of Some Of The History Of ZLW Wellington Radio has been searched out by Elsa Kelly and put in Web useable form by her father, Jamie Pye ZL2NN. Thank you Elsa Kelly.

From the “Evening Post” for 3 August 1974

ZLW WAS NEW ZEALAND’S FIRST OFFICIAL RADIO STATION

The text below is based on a report written by Nigel Fitzgerald

Building and Location

The start of ZLW began in July 1911 when young men appeared on top of the General Post Office, doing work in the clock tower. This was when the spark transmitting equipment was installed amongst the clock’s wheels, drums, chains and cogs. The three–storied clock tower was also used as one of the antenna supports.

Picture 1: The General Post Office in 1907

The picture comes from a link to the Alexander Turnbull Library and is titled:

Chief Post Office, Customhouse Quay and Post Office Square, Wellington

details of the image are available by clicking the picture

Picture 1 shows how the building looked in 1907 with the clock tower being the dominating feature. This building was demolished and replaced in 1987 by the five star Parkroyal Hotel shown below in Picture 2.

Picture 2: The InterContinental Parkroyal Hotel is now on the site once occupied by the General Post Office

Picture 3: General Post Office Location as a red coloured square.

Picture 3 has a map showing the location of the site where NZ’s first official radio station shared a tower with the town clock of Wellington City. This sharing arrangement lasted a year until ZLW Wellington Radio was shifted to Tinakori Hill. The site in the clock tower proved to be a poor radio site especially for reception. There was considerable disturbance from such things as the GPO clock itself and the electric tramway that ran past the building. Also the station had great difficulties in both transmitting and receiving in some directions and to a gradual loss of signals at short ranges. These effects were put down to the surrounding hills around Wellington.

The Opening of Wellington Radio in the GPO

The opening celebration on the 26 July 1911, appeared to be an internal function within the Post Office as no press were invited, nor was there any statement issued that the radio station existed.

Putting the radio station in an existing post office building would have been to save expense and to ensure that the existence of the radio station was kept under wraps. This was proven by the appearance in the Evening Post, the day after the opening, a seven and a half line advertisement that stated that: wireless messages can now be accepted for transmission by the Post Office. The statement gave nothing away and went without press comment.

However, there had already been a celebrated exchange of greetings between ships, one in Wellington harbour, another at Port Jackson (Sydney, Australia), and a third acting as a repeater at sea.

There was another item in the press at the time concerning what was considered the strange behaviour of ship’s wireless operators, some of whom refused to answer when called at sea by other ship wireless operators. This was due to the fact that Marconi–trained operators were not allowed to communicate with any wireless station other than a Marconi station.

Another story brought in a local touch. On July 27 the day after the clandestine opening of Wellington Radio the RMS Ruahine arrived from London with a wireless telegraph installation that had been fitted at that port. All three Wellington papers made much of the fact that the Ruahine had thus become the first of the New Zealand Co’s vessels to be so equipped.

By this time the operators in the Post Office tower had begun their great adventure. In the words of the official report they successfully carried on radio communication at night over a normal range of 600 miles. This bold statement very properly minimises both the difficulties and the achievement.

In fact a much greater range than 600 miles was attained at night with a clear signal in directions that did not include the west where the hills press close.

Notes prepared for the Postmaster–General at the time refer to great difficulties experienced in both transmitting and receiving in some directions and to a gradual loss of signals at short ranges.

The Move To Tinakori Hills

The hours of opening were from 8.00 am to midnight, 16 hours of which only one was unaccompanied by quarter hour chimes and booming hour bell.

For that one hour as night, conditions were usually perfect.

It was, therefore, all the more irritating to lose communication with ships from the west.

These ships were generally picked up a few miles off the Australian coast and held in contact to a point rather less than one day’s steaming from the Port of Wellington where signals, in the vast majority of cases were, deflected from their true course at such an angle that Wellington Radio was unable to receive them.

The station would have to be moved.

There was nothing else that could be done to the equipment that was available at the time, though modern high frequency stations have been able to overcome such problems. (And bringing the story up to the 21st century, communications via satellite gives 24 hours, seven days a week service, without any concern to the frequency of operation or the time day or night, winter or summer.)

At least one highly qualified and experienced radio man, at the time, firmly holds that all short range communication between Wellington and shipping to the westward comes by the long path, that is, completely around the earth in a westward direction and arriving via the east in Wellington.

When the Wellington Radio was moved from the clock tower to Tinakori Hill, on October 14, 1912, this was no fly–by–night affair but an occasion for sunlight, bunting and competition between the eminent speech–makers.

Picture 4: The Opening of Wellington Radio with the buntings and wind.

I wonder what the dog thought of the goings on?

The picture comes from a link to the Alexander Turnbull Library and is titled:

Radio Telegraph Station, Tinakori Hill, Wellington 1912

details of the image are available by clicking the picture

Wellington’s wind blessed the opening with a 70 miles an hour gale. The 70 miles per hour was not an estimated wind velocity but the first official recording of the new anemometer.

The most distinctive parts of the layout were the twin masts of Oregon pine, 150 feet in height, that dominated the site. The new station, far removed from chimes and tramcars, had the even greater advantage of its height, 985 feet above sea level, which gave it an unshadowed view in all directions.

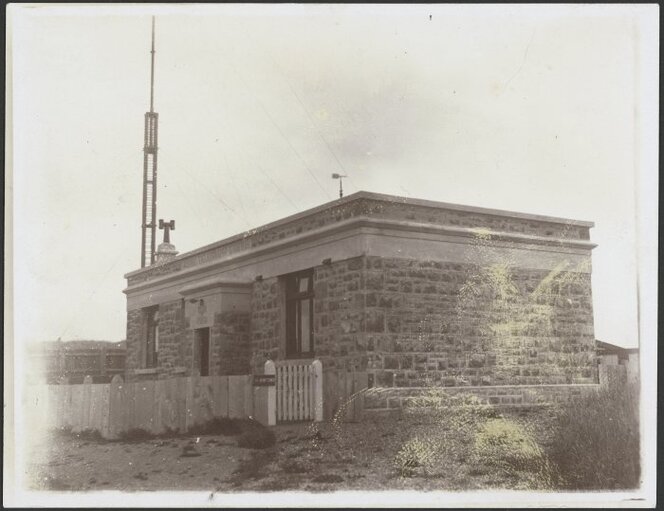

Picture 5: Wellington Radio 1912 showing the Oregon pine mast on the left of the picture

The picture comes from a link to the Alexander Turnbull Library and is titled:

Government radio telegraph station, Tinakori Hill, Wellington – Photographed by Mrs Orchard.ca 1912

details of the image are available by clicking the picture

Within a few hours of opening, the station had uninterrupted communication with stations at Sydney, Melbourne and Hobart. With Suva at a range of 1500 miles, and with a number of ships at sea at distances of well over 1000 miles. Macquarie Islands, as well as many other stations, remarked on Wellington Radio’s greatly improved signal.

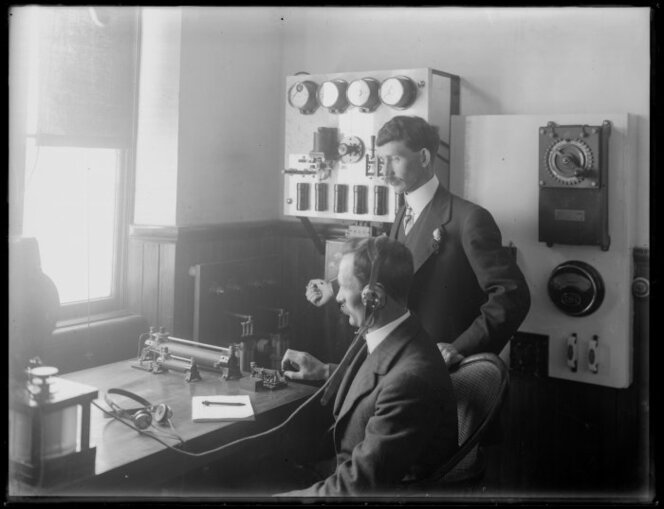

Picture 6: Interior of Mount Etako (also known as Tinakori Hill) station, and (employees?) Wellington Radio, circa 1912. Men unidentified. Photograph taken by Sydney Charles Smith

The picture comes from a link to the Alexander Turnbull Library and is titled:

Government radio telegraph station, Tinakori Hill, Wellington – Photographed by Mrs Orchard.ca 1912

details of the image are available by clicking the picture

Back to top

From the “Evening Post” for 27 March 1912

WIRELESS TELEGRAMS

The following return has been furnished by the Postmaster–General of paid business transacted at the Wellington wireless telegraph station during the seven months ended 29th February, 1912.

The station was opened on 26th July, 1911: Number of messages forwarded and received, 746; number of words, 7951; revenue, £303. In addition, there are approximately twenty–four free messages relating to shipping and twelve free weather reports received each month. The Wellington radio station has successfully signalled a message to a ship 960 miles out, and on one occasion received a message from the s.s. Ulimaroa when that vessel was one day out from Hobart, or, approximately, 1150 miles distant from Wellington.

Back to top

From the “Evening Post” between 13 May 1926 and 17 May 1926

THE WIRELESS STATION SERVICE NOT INTERRUPTED

Without any loss of time the Telegraph Engineers’ Department of the Post and Telegraph Department set to work to relieve any embarrassment wireless traffic was made subject to in consequence of the collapse of the aerial mast at the Tinakori Hills Station on Wednesday. An impression was abroad that the service had been stayed as a result of the trouble, but the authorities state definitely that the service suffered no important interruption, as immediate expedients were put into operation to maintain the traffic, though only in a limited sense. An aerial was at once erected to enable the station to communicate with Awarua and Auckland, which in turn took up the traffic which in normal circumstances is conducted at the Tinakori Hill Station. Temporary masts were erected today, and will serve until a new structure is obtained.

The department authorities are quite satisfied that the temporary arrangement will fulfil all necessary requirements. The collapse of the big tower came as a surprise to the officers of the Telegraph Engineers’ Department. It was built to a standard which is utilised in countries as far distant as Alaska, and is of a type constructed to resist the climate conditions of either tropical or cold regions. In expert circles it is generally conceded that had the gale of Wednesday been of consistent velocity the worst would not have happened. As it was, the wind came in cyclonic gusts and gradually broke down the resistance of the fastening of the tower. The structure itself was apparently undamaged by the wind, but the fall completely wrecked it. The tower weighed about four tons.

Time Signal Service

In addition to wrecking the tower of the Tinakori Hill wireless station, the gale on Wednesday broke the telegraph line by which the daily official time signals are sent from the Kelburn Observatory to be transmitted by wireless for the benefit of ships at sea. The signals, which go out daily, at 10.30 am and on Tuesdays and Fridays at 8.30 pm, could not be sent yesterday, but the line has been repaired, and this important aid to navigation was available again this morning.

Broadcasting Not Checked

Although the gale carried away the aerial of the broadcasting station and threatened to interrupt the service for a day or two, no stoppage actually occurred. Wednesday is not a transmitting night, and yesterday local management of the broadcasting company was effectively assisted by the Post and Telegraph Department to make good the damage at least for the time being. The usual Thursday programme was consequently transmitted. During the evening the announcer expressed the thanks of the management to the Department for its prompt and valuable assistance in repairing the damage.

VLW and 2YK Crippled Aerial Blown Down By Gale

VLW = ZLW

The gale yesterday caused a mild sensation by blowing down the tower of the Government wireless station, VLW, and left the hilltop looking singularly bare. Less notice was taken, probably, on the fact that the aerial of ZYK, which was supported on masts on the “Dominion” office, was also carried away, though fortunately the masts were not broken. Wellington is therefore temporarily without a wireless voice. All speed will be made with the restoration of the broadcasting aerial, which will have to be completely renewed.

The destruction of the tower of VLW recalls the curious theory recently advanced that the interference which has been experienced by users of sets not highly selective from that station signals was caused by radiation from the stays of the masts. The tower was entirely self–supporting, being a rigid steel lattice structure, pyramidal in shape and about 160 feet high. The so–called stays were the aerial, so that the interference and the signals themselves undoubtedly came from them; but to blame them as stays was, of course, absurd. The aerial wires took no share in the supporting of the tower.

Widespread Storm Heavy Gales And Rain

Much Damage Reported Wellington Under The Blast

Yesterday’s storm was not only severe but extensive, as the telegraphic reported show, and much damage was done by the gale and by the floods caused by prevailing and recent rain. The flood damage was most marked on the West Coast and in North Canterbury but the storm seems to have enveloped the greater part of the Dominion.

The heavy gale in Wellington all day yesterday played havoc in the city and suburbs with fences, chimneys, and small buildings of frail construction. The most serious effect of the storm was the destruction of the steel tower of the wireless station on Tinakori Hills. The gale blew there at a velocity of 100 miles per hour. The Chief Telegraph Engineer, Mr A Gibbs, inspected the damage and found that the holding down bolt on the windward side had been torn away. The tower was badly buckled by the fall.

Without any avoidable loss of time an emergency aerial was erected to permit of the service being resumed. A gang of men was sent out and soon put up the temporary aerial. Until arrangements are made for the re-erection of the tower, the present temporary structure will suffice to meet demands.

The Present Conditions

The cyclone passed south of Cook Strait last evening, and the wind moderated this morning this morning, although there is still a considerable gradient in the barometric pressure in the Dominion. Velocity of the wind yesterday was highest between 2 o’clock and 3 o’clock, according to registration taken at the Thorndon Observatory, and the wind was of an extremely gusty character, the pressure ranging from one-third of a pound to ten pounds per square foot, or from a velocity of less than ten miles per hour to nearly sixty miles per hour. The Government Meteorologist (Mr D C Bates) states that the pressure recorded was not so heavy as most people would imagine. He had a record where the pressure went up at one time to 45 pounds per square foot. The pressure in yesterday’s storm would be about 25 pound per square foot. When the wind died down yesterday the average for 24 hours was actually less than on the previous day, when 451 miles were recorded. While on the 9th May, although a steadier wind prevailed, 478 miles were recorded. Today broke fine and clear, though towards the afternoon the conditions become colder and overcast.

The Official Forecast

Stormy weather and heavy rain has been experienced in many part of Dominion. In Wellington 0.44 inches was registered, 0.06 inches at Foxton, 1.2 inches at Westport, 0.5 inches at Greymouth, 5.16 inches at Arthur’s Pass, 3.6 inches at Rakihiroa (Gisborne). Snow fell today at Bealey and the Hermitage, and snow on the ground is reported from Otago. The forecast is for westerly winds, strong to gale, backing to southerlies, with squally weather and heavy showers, and a cold night in expected generally with more snow in the South.

2YK Recovers in Time

The Government wireless station on Tinakori hills was not the only wireless establishment to lose its aerial yesterday. The antenna of the Wellington broadcasting station, 2YK, came down. The masts were uninjured. A broadcasting aerial is no simple thing, and it seemed as if the service would be interrupted for a few days. It was stated this morning, however, by the local manager of the New Zealand Broadcasting Company, that in all probability the damage will be at least temporarily repaired in time for the usual programme to be broadcasted this evening.

The Time Signals

Contrary to anticipation, the engineers of the Post and Telegraph Department were unable to complete the repairs of the land line between the Dominion Observatory and the Tinakori Hills Wireless Station yesterday, and in consequence, the time signals were not transmitted in the morning. The line, however, was restored late yesterday, and the usual evening time signals were sent out at 8.30 pm.

Wireless Mast Blown Down

A gust of wind of exceptional strength and severity demolished the steel aerial mast on the Tinakori Hills at about half past two o'clock this afternoon. No damage was done to the brick building beneath the aerials, but the station was naturally thrown out of action.

The secretary (Mr A T Markman) immediately gave instructions for the wireless stations at Awanui and Awarua to be informed by telegraph that the station was out of action, and to advise shipping accordingly.

The mast, designed as a self-supporting structure, and unstayed, was about 150 feet in height. It supported four wires, stretched out at an angle to form an umbrella aerial. The crash of the falling structure was heard in the city.

The Government Meteorologist stated this afternoon that the wind was not of extreme velocity, but very gusty.

Visitors To The Wireless Wreck

To take advantage of the beautiful windless and cloudless day, many hundreds of people yesterday afternoon climbed to the top of Mount Etako, on the Tinakori Hills, to inspect the ruins of the wireless mast which was blown down in the heavy northerly gale of last week. From the time the trams commenced running in the afternoon until after sunset a steady stream of people passed though Northland and up the steep slopes of the hill. The day being ideal for walling, many of the people walked along the ridge of the Tinakori Hills to Wadestown, taking the tram from there back to the city. “It’s an ill wind that blows nobody any good,” but the gale of last Wednesday must have been directly responsible for blowing a good many pounds into the coffers of the tramway department yesterday–at any rate so far as the Northland and Wadestown sections of the tramway system were concerned.

Back to top

RADIO SIGNAL PROPAGATION OBSERVED DURING AN ECLIPSE IN 1930

A COOPERATIVE EXERCISE BETWEEN THE NEW ZEALAND POST OFFICE AND THE DSIR

Cooperation

The New Zealand Post Office cooperated with the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) with the object of investigating the influence on propagation of wireless waves of the solar eclipse of October 1930. This eclipse, it will be remembered, was observed and photographed with success by Dr D E Adams, Dominion astronomer, and his party who went to Niuagou Island for the purpose. The scope of the tests, which could be arranged, was limited by various factors. In the first place, the path of totality passed across the Pacific Ocean, so that the choice of observing stations in close proximity to the band of totality was necessarily restricted, more particularly as only certain islands are equipped with wireless apparatus. Secondly, it was not possible to send investigators with special equipment to any of the islands, so that it become necessary to adopt the method of aural estimation for recording of signal strength, the regular operators at the various stations caring out the work. Moreover, the distance of transmission was, inevitably, considerable in many cases.

Test Stations Details

Special transmissions were arranged from the following stations:–

Apia Radio ZMA, 850 metres, 100 watts;

Suva Radio VRP, 800 metres, 5000 watts;

Apia Radio ZMA, 52 metres 500 watts;

Wellington Radio ZLW, 51 metres 5000 watts;

Papeete Radio FPB, 40 metres 200 watts;

Papeete Radio FPB, 24 metres 200 watts;

Apia Radio ZMA, 19 metres 1500 watts;

Wellington Radio ZLW, 19 metres 500 watts.

Test Stations Transmission and Receiving Details

During the tests the special transmissions consisted of a series of ten minute signals followed by periods of five minutes silence, the transmissions taking place during the periods 0 to 19, 15 to 25, 30 to 40, and 45 to 55 minutes past the hour respectively, except that in the case of Suva Radio VRP, on 800 metres, this schedule was retarded by five minutes throughout.

The receiving stations interested in the experiments were numerous and were dotted round and in the Pacific and all over New Zealand. The tests included observations on long waves (11,5000 metres), on medium wave–lengths (850 and 800 metres), and on short waves (52 to 16 metres). The transmission paths lay in the Pacific Ocean region, and in the majority of cases crossed the line of totality of the eclipse. The measurement of signal strength was based on the method of aural estimation. The signals received during the eclipse were compared with those recorded at similar times of the day preceding and following respectively. Experienced coast station operators working with frequencies used by them daily, and using receivers with which they were thoroughly familiar made the principal observations. Moreover, in each particular case the same receiver was used throughout the tests, so that the figures obtained on the days preceding and succeeding should be comparable with those obtained during the eclipse.

Results of The Test

Summarising the results of the tests, Dr M A Barnett says that the results were in general accord with those experienced during previous total solar eclipses. No effect definitely attributable to the eclipse was observed on long waves, although on the Ruby-New Zealand transmission a definite increase in strength occurred during the eclipse period. On the 850 and 800 metre wave–lengths an effect equivalent to a partial return to night time conditions as shown for transmission distances lying between 600 and 1200 miles. This effect was noticeable whether the transmission path actually crossed the line of totality or not. the maximum change in the signal strength occurred approximately at the time of minimum eclipse effect between transmitter and receiver, although in certain extreme cases the records indicate a lag of as much as thirty minutes between the two phenomena.

In general, no eclipse effect was observed on short waves, except in certain cases on a wave–length of 53 metres, when a partial return to night time conditions was definitely indicted. In this case also the maximum effect on signal strength either coincided with or lagged slightly behind the maximum of the eclipse at a point midway between transmitter and receiver.

During the tests records were kept of the strength and persistence of atmospherics, but an eclipse effect was found only in the case of reception on 850 and 800 metres wave–length at points in the neighbourhood of totality, when a slight increase in strength of atmospherics was observed during the maximum o the eclipse. In genial, it may be said that the effect of the eclipse was to produce a partial return to night time conditions as far as wireless transmission was concerned, and that the resultant changes in signal strength followed fairly closely the equivalent changes in the amount of solar radiation reaching the atmosphere. There are indications, however, in certain cases that the effects produced a lagged, in time, slightly behind the corresponding change in the amount of solar radiation reaching a point midway between transmitter and receiver.

Back to top

From the “Evening Post” for 16 September 1931

THE INAUGURATED RADIO–TELEPHONE

CALL BETWEEN ENGLAND AND NEW ZEALAND

This call took place via ZLW

The Call is Between The Governor-General (Lord Bledisloe) of New Zealand and a Correspondent of the “Evening News” London England

Start of Radio-telephone Call

“Evening News New Zealand waiting.”

I had put a call to Lord Bledisloe, Governor-General of the Dominion of New Zealand from my Office at the Evening News in London. The time is 6 a.m. Three minutes afterwards the telephone bell rang and on lifting the receiver, I was told that I was “through”.

“Hello”, came a cheery voice, as clear and plain as though it was coming from a local London call. “Is that the Evening News London”?

“Yes” I replied. “Is that Lord Bledisloe?”

“It is,” he said. “Good afternoon.”

“Good morning,” I answered, and we both laughed.

“I had forgotten the difference in the time for a moment,” said the Governor-General. “It is about 4.30 p.m. here.”

And so the new radio-telephone service between England and her furthest Dominion, New Zealand, was inaugurated. My call was the first public call made either from this country (England) or New Zealand. It is the longest direct telephone service in the world, and only one other station was used in the transmission–that at Sydney, Australia. The distance is about 12 000 miles.

“Isn‘t It Wonderful?”

Lord Bledisloe had evidently the same thoughts as I had on this latest wizardry of world communications.

His next words were, “Isn’t this wonderful! here I am at government House, Wellington, and you are at the Evening News office in London, and we are talking to one another as easily as though we were only 12 instead of 12 000 miles apart.”

“Wonderful, wonderful,” he repeated.

For several minutes we continued our conversation, and the hearing was perfect, “Can you hear me all right?” he asked. “I am getting you splendidly.”

I told him reception was as good on my side, and he asked me what kind of weather we were having in the old country.

“It has been rather a wet summer, so far,” I said, and Lord Bledisloe laughed. “Nothing new in that for England,” he said. “Here we are experiencing the most delightful weather, and we had the best winter that anyone can remember.”

“Have you recovered from the earthquake disaster in the North Island?” (Napier Earthquake) I asked.

“Oh yes,” Lord Bledisloe said. “It has left its mark, of course, but New Zealanders are people of pluck and resource, and we have got over the catastrophe.”

I said that we knew something here of the pluck of New Zealanders from the performances of their cricket team.

“Ah!” said the Governor-General, and I could tell from the tones of his voice how great was his interest in this subject. “They are not doing badly, are they? I see they are to have two more Tests, and I am hoping that they will win the next one.”

“It would be a fine feather in our cap if we, a country of one and a half millions of people, beat mighty England. I think our team is a good one and they are well led by Mr. Lowry.”

The Governor-General, in reply to another question, said trade was none too good in the Dominion.

“But it will be better,” he added, “and we are holding on. You tell the Old Country that when it wants wool, butter, cheese, and meat to think of New Zealand.”

He said the Hoover plan for restoration of world prosperity, and the Seven Powers' Conference in London, were being followed with the greatest interest down under.

Value of the Service

“Do you believe the new telephone service will be of material advantage to New Zealand?” I asked.

“Certainly,” replied Lord Bledisloe.

“Quick communication of that kind must be good not only for Governmental purposes, but for business also.”

“But we are poor men here, and I hope the cost will be cheaper soon.” (The charge is £6 15s ($13.50) for three minutes.)

“It has been a most interesting conversation,” he continued, “and I am glad the Evening News rang me up. You were the first in the field.”

“Good afternoon! I mean good morning!”

And a hearty laugh, 12 000 miles away, was the last sound I heard as I hung up the receiver.

Back to top

From the “Evening Post” for 9 June 1934

MAN WITH HIGHEST JOB IN WELLINGTON

WIRELESS SUPERINTENDENT TALKING TO THE WORLD FROM TINAKORI HILLS

On the Tinakori Hills–ZLW Wellington Radio

This serves to introduce the man with the highest job in Wellington–Mr J H Hampton, superintendent of the Government wireless station, 960 feet up on Tinakori Hills. He customarily talks in dots and dashes, but can speak English when he takes off the headphones.

Within the station reserve of 30 acres there are two buildings, one close to the foot of the 165 feet high trestle mast that is a landmark for miles around the city, the other standing a few chains down the slope. In the lower one a Frenchman was talking loudly, volubly. He was being emphatic about something, as Frenchmen sometimes are. Mr Hampton moved a switch, and the short–wave broadcast from Paris ceased. A young man with headphones on and a hand at a Morse key was exchanging weather reports with an intercolonial liner

If the radio men on the Tinakori Hills do not yet have televised eyes for the shipping world they have the ears for it. On Thursday, May 31, the Rangitiki cleared London’s docks en route for New Zealand. Wellington Radio has talked to sparks in the ship’s wireless room ever since the vessel turned down the Thames towards the Southern Hemisphere. Short–wave magic has made this possible. And as she steams through the Atlantic for New Zealand, the Rangitiki has received and given weather information, accepted radiograms for people on board. Nightly, too, Wellington Radio has conversed in Morse language with the Aorangi voyaging from San Pedro to Honolulu.

Magic of the Air

They can do anything these wireless men–or so it seems. It is hey presto this and hey presto that–Wellington days and Arabian Nights. The impossible of yesterday is the commonplace of today.

Talking with the ships is so important an aspect of government wireless work that an operator is assigned to the duty exclusively. Throughout the 24 hours of the day a man is listening in to the da–dada–da–da flung into the ether by a score of ships. He listens particularly for the distress cry dit–dit–dit–dar–dar–dar–dit–dit–dit (SOS). Happily it is rarely heard.

Silent Periods

By international agreement a profound hush falls on the wireless world of ships twice every hour. For two periods of three minutes each and at times synchronised on the seven seas, a Great Silence is observed. The air is cleared by one consent of all messages on the 600 metres wave–length. This is the moment when a vessel in trouble can be sure that her SOS is heard. It is done to enable ships with low power equipment to call for assistance. On a clock in the wireless room, the clock is marked at 15 to 18 minutes past the hour and 15 to 12 minutes to the hour, as being the silent periods.

Back to top

From the “Evening Post” for 9 March 1938

LANDMARK TO FALL AWARUA RADIO MAST RELIC OF EARLY SYSTEM

(Special to the “Evening Post”)

Invercargill March 8

The 400 feet steel tower which has served the Government wireless station at Awarua for the last quarter of a century, and which during its lifetime has seen marvellous development in the radio world, will be brought to the ground within the next few days. It has outlived its usefulness. A change–over to shorter aerials more suitable for short–wave reception and transmission has already been effected. The tower has been a prominent landmark in the thinly–populated plain between Invercargill and Bluff since 1913.

Access To Photos Of Mast Coming Down And Site

One hundred and twenty tons of steel will come to earth with a crash when the tower is released from its stays. The steel will be sold.

The great height of the tower was necessary when it was built. In the earlier days of wireless it was necessary to use very long wave–lengths to transmit for great distances but with the advent of the short–wave transmitters even greater distances can be covered with lower power and smaller aerials. Whereas even with the help of the tower it was not possible to reach more than half of the world, nowadays, which modern improvements, Awarua station can communicate with any part of the world with a fraction of the power previously used.

The new aerial towers, of which there are nine, range in height from 40 feet to 70 feet, and permit the receiving and transmitting services to be separated. If the conditions are good, simultaneous transmission and reception can be carried out.

The 400 feet tower is a triangular girder about five feet across, and is supported on a pivot resting on glass insulators. At its top is a small platform with a railing round the edge. Even good climbers used to scaling heights take over a quarter of an hour to reach the top, which is liable to sway about two feet in rough weather. The tower is supported by two sets of three stays, the first being attached at 100 feet from the ground and the second at 300 feet. The last 80 feet of the tower is not supported.

Ever since the station has been established at Awarua the locality has been known as the best in the world for reception. The station site has also the advantage of not being screened by mountain ranges and of having a fairly good type of earth. On this account Awarua has received messages that the other two Government stations in New Zealand (at Auckland and Wellington) have failed to received.

Press Messages Handled

Awarua has been able to handle all messages for undertakings such as the Byrd Expedition to the Antarctic and the flight of the Centaurus and the American Clipper ships. It is regular in touch with ships in all parts of the world and the volume of business done in this way has increased enormously in recent years.

The improvements in radio transmitters have meant that more messages can be handled in the same time and with the same staff as was necessary in the earlier days of longer wave–lengths. The present staff of nine at Awarua is not appreciably greater than when the station was opened in 1913. Awarua is the last of the two original stations erected by German contractors in 1912. The other station at Awanui, North Auckland, which was dismantled and the equipment disposed of about 10 years ago. The work which Awanui station performed is now done by a smaller station in Auckland City. Wellington is also equipped with a group of stations which handle a great deal of radiotelephone work, as well as commercial Morse work for ships.

Back to top

From the “Evening Post” for 24 June 1939

ERECTION IN 1939 OF THE SIX STEEL MASTS

WET WEATHER DELAYS HOISTING TO UPRIGHT POSITION

Because of the wet weather of the last few days the work of painting the first of the new masts for the Government communications wireless station on Tinakori Hill has been held up, and it will be some days before the mast will be ready for hoisting to the upright position. It was to have been erected yesterday, but it would not have been hoisted if had been ready as the day was not sufficiently calm.

Picture 7: Six towers at ZLW photographed in 1963 and marked with white vertical bars

The mast, which is the first of six which are to be erected in a row along the ridge, will be 155 feet high. It weighs 10 tons. Another mast is being assembled on the hill and the parts for the other four are being made in the workshops of the contractors.

The task of hoisting the completed mast to the upright position is a difficult one, and cannot be underaken if there is a wind of more than 25 miles an hour. It is carried out with the use of an electric winch and flexible steel hawsers.

Back to top

From the “Dominion” for 5 May 1975

DISMANTLING IN 1975 OF THE SIX STEEL MASTS TOWERS TUMBLE

Picture 8: Towers Tumble

A puff of smoke drifts away as one of the two old broadcast aerial towers on Tinakori Hills falls to the ground. The towers were demolished by 40 territorial soldiers from the 6th field squadron of the Royal New Zealand Engineers on Saturday on a request from the Post Office, which wanted the site for a new aerial system. Explosives were wrapped round each leg of the tower giving a clean break. Each tower fell on a pre–arranged path. Special care was taken to avoid a house seventy–five yards away.

Back to top

The New Zealand Herald 27th April 1948

NEW BUILDING PLANNED FOR RO ZLW RADIO COMMUNICATION STATION AT WELLINGTON

[By Telegraph – own correspondent] Wellington, Thursday

Additional accommodation has become necessary at the Tinakori Hill radio station, and tenders have been called for the work. It is not necessary to add to the antennae. The present system, though simple, is doing the work. It is in order to keep pace with more modern methods of signalling that increased accommodation is necessary.

The new building will be used primarily as a receiving station and will therefore be erected at a little distance from the transmitter. It will be possible to work with shipping, coastal stations, Samoa, Rarotonga and the Pacific Islands simultaneously.

Back to top

From the “Evening Post” around 1950

WORK OF MAKARA RADIO STATION

THE EAR THAT HEARS THE SOVIET SATELLITES

Radio Ear For New Zealand

As the official ear of New Zealand the work of the Post Office’s radio receiving station at Makara has been brought into the news through receiving signals from the Russian satellites

This station is the major receiving centre of overseas telecommunications just as the transmitting station at Himatangi is the country’s voice. Makara keeps in radio contact with the rest of the world is located in hilly country 11 miles west of the General Post Office in Wellington. The Makara station property covers 2300 acres, much of which is taken up by the extensive aerial arrays necessary for directional reception from various parts of the world.

The Aerials

The imposing array of aerials include 54 new inverted Vee aerials supported from four 100 feet high trellis steel towers and arranged to provide directive reception throughout the full 360 degrees. Some of there were erected specially to improve reception for the satellite signals. There are two large broadside arrays beamed on Australia and two rhombic aerials beamed on the American continent. These are used for reception of radio-telephone, telegraph and picture transmissions from those countries.

Shipping Watch

Other aerials designed for reception on lower frequencies are used for receiving radio signals from shipping and to provide a constant listening watch for distress or emergency calls, Radiotelephone, telegraph and picture reception services between New Zealand and the United Kingdom, Australia, America, and even the south Polar Regions are routine.

The duties for the staff of 17 station technicians, who between them maintain a 24–hour service under the control of the senior technician, Mr C Askey. An impressive total of 55 radio receivers, working in various combinations enables, besides conventional radio reception, radio-telephone, picture, telegraph and teletype reception. For instance, not only news pictures come in as radio signals here, but finger prints for the police and trade statements for New Zealand companies overseas.

Quartz Hill

Quartz Hill is the New Zealand Broadcasting Service Makara Receiving Station, now in use as ZL6QH by the amateur radio service. It is located about 1.5 km from the Post Office radio receiving station.

Back to top

From the “Evening Post” for 18 August 1956

STATION ZLW TREES IN GROUNDS, PLANTING IN HAND AND HOUSE FOR CARETAKER

If the winds which whistle and wine in the high steel–latticed aerial mast of the commercial radio station ZLW on the Tinakori Hills, or Mount Etako, are not cruel, Wellington citizens and visitors to the capital may in time to come see the hillside immediately below the station ablaze with the scarlet blooms of the pohutukawa and of flowering gums. The post and telegraph Department have in hand an extensive tree–planting scheme for this area, provision having been made for putting in of several thousand trees. Already about 100 pohutukawa trees have been planted. A number of other trees are also in, and all around the station are holes, several thousand of them, waiting to receive other trees as they come to hand. Something like 5000 trees, a large proportion of them flowering gums which in later years perhaps may coax the Tui to sing in their branches, are to be planted this season, and it is hoped to have others available for next year. The success of certain trees in the Botanical gardens and at the Karori Reservoir has been largely used as a guide in the selection of those for the top of Tinakori Hill. Not only are the young trees being planted around ZLW, but a nursery is also being prepared in a slight depression with a view to rearing trees under conditions similar to those prevailing further up the hill so that they will be hardy young specimens when the time comes for them to be planted out.

Back to top

A very solid residence for the caretaker, who at present time lives at Melrose, is being built on the hill. When this building is completed it will be a stout snug home from which will be seen probably the finest panoramic view of Wellington it is possible to get. Since the solid and compact stone building on the ridge was completed in 1912, radio development has demanded considerably more space, with the result that the original building is now used solely to house the transmission apparatus, while lower down the hillside is another building larger in size which provides spacious and comfortable accommodation for the staff of the receiving and traffic–clearing section of the station. In this building beds are provided so that if it is a very stormy night when operators go off duty, or for other reasons, they may spend the night there.

Back to top

A Busy Station

ZLW is maintained by the New Zealand Post Office as a national safety service rather than as a profit making branch, but it is one of the busiest telegraphic centres of the Dominion, being staffed in shifts throughout the 24 hours of the day. Regular contact is maintained with the islands in the southern Pacific and the Chatham Islands, and since the establishment of the air services by Union Airways and Cook Strait Airways the station has fulfilled another important function. The transmitting apparatus is something which anyone interested in radio would find a joy to inspect. There are something like 15 transmitters in the building on the ridge of the hill. Both buildings are stoutly constructed and they need to be, for it can blow very fiercely in these parts. Once inside these buildings, no matter how hard it may be blowing outside, all is comparatively peaceful, except for the talk of the instruments, but compared with the noise of the wind howling around the aerial mast, the top of which is 1150 feet above sea level, their talk is as music to the experts ears. There are sudden clicks and other noises in the transmitting house it is true. They sound perhaps a little eerie until one becomes accustomed to them. Indeed it is related that they have made many a visitor to the station “jump”

Back to top

While viewed from the city the station looks a long way up, many visitors to Wellington make the trip there, either by walking up the track from Tinakori Road, or by going by tram–car or motor–car by way of Northland. The caretaker says that the hill work makes one very fit. It can be recommended–for those who want to get thoroughly fit.

When the additional provision was made at the station for the receiving work the material for the building had to be sledged up, but since then the track from Northland side has been widened to enable motor traffic to use it, but that does not mean that the road is open to all motorists. It is government property and so far as motorist are concerned, the road is for use for those on official business only. Cars may be driven right up to the foot of it. The walk to the top is not far, and the view of Wellington and its environs from the top is more than a fitting reward for the exertion involved in the climb.

Back to top

From the “Evening Post” for 19 February 1968

SATELLITES HAVE NOT TAKEN OVER RADIO COMMUNICATIONS

Radio Still Used

In these days of global television links through orbiting satellites, conventional steam radio has been thrust into a back seat but it is still the basic means of international communication.

Just how important it remains can be judged by visiting Wellington Radio, the complex of weatherboard buildings and nissen huts dominated by a 160 foot steel mast on Mount Wakefield, better known as Tinakori Hill.

Here Post Office operators maintain a round–the–clock service vital to the safety of thousands of people at sea in a massive area stretching from Hawaii to the southern polar regions and from mid–Tasman across the Pacific Ocean to South America.

Traffic handled by Wellington Radio is immense. Last year (1967) 69 900 messages were either transmitted or received. In addition to an internal service relaying earier reports during the summer period of high fire risk. Wellington Radio is one three stations in New Zealand – one is at Auckland and the other is at Awarua, near Bluff–which form the hub of a communication centre responsible for one of eight sectors in a world network.

Must Report

When a British ship crosses a sector boundary line it must notify the responsible centre of its position and give certain other information, including weather conditions. Thereafter, if in an appropriate sector, it listens to four–hourly messages transmitted from Wellington Radio.

Although vessels sailing under other than British flags are not bound to contact the sector centre the majority do as a matter of course. To assist in plotting positions, and as a means of easy reference in an emergency, Wellington Radio has a large operations map to which metallic markers are a attached and moved, using the information supplied in the bulletins.

The superintendent of Wellington Radio (Mr J F Ryan) said that on an average day the map would be dotted with about 30 markers. But the map, which forms a spectacular focal point in the transmitter room, it is not essential.

“Perhaps we could get along without it,” Mr Ryan said. “It requires a lot of work to keep up to date but, against this, it is extremely useful aid in assessing a ship’s position quickly. I am of the opinion that it is worth the work involved.”

Emergency Messages

While by far the bulk of Wellington Radio’s dealings are in routines matters, emergencies occasionally arise. Fires, sickness, engine failures and storm distress–these are some of the common subjects of emergency signals received at Wellington and the other two New Zealand stations.

Operators have a set of procedures to follow, depending on the location of the ship. This mainly involves beginning the train of events, which leads to an air-sea rescue operation.

Frequently Mayday messages are received from ships in distress near the coast of another country. In these situations the operators usually record the Morse message, but can do little else but sit in on the drama happening thousands of miles away. The ability to span huge distances with a few taps of a Morse key is one of the fascinations of radio. To the men of Wellington Radio, transmitters and receivers are more than tools of trade, for like radiomen everywhere, they are enthusiasts. This probably accounts for the high reputation for efficiency enjoyed in international marine circles by this lesser known department of the Post Office.

Back to top

From the “Karori News” For 27 October 1980

WHAT ZLW WAS LIKE IN THE 1980s

Most Wellingtonians would probably be aware of the existence of a radio station on Tinakori Hill, as the aerial arrays and masts just below the crest of the hill are visible from many parts of the city.

Northland residents in particular will also know of the very steep access road to the station and its houses which rises sharply from Orangi Kaupapa Road, but perhaps fewer will know of the functions of the station.

Wellington Radio ZLW is one of four coast radio stations within New Zealand owned and operated by the NZ Post Office. The other three are Auckland radio–ZLD, Chatham Islands Radio–ZLC and Awarua Radio–ZLB.

Back to top

Coast Radio Stations are synonymous with safety of life at sea. Any small boat owner, caught with an empty tank will tell how it feels to know that professional help is available through a coast station.

But is not only small boats that can run into trouble – ships range in size from the giant super tanker to the small runabouts – are just as prone. Hazards faced by shipping are reflected in figures put out by Lloyds of London who reported that in one 12–month period there were 400 maritime casualties. Three of these remain unsolved. The ships have just disappeared without trace.

The need for coast stations is obvious despite the cost. In New Zealand coast stations answer one emergency call a day ranging from minor to life and death situations. It is mandatory for some classes of vessel and ships over a specified tonnage to fit radio equipment However, smaller vessels, such as pleasure craft are encouraged to fit radio for basic safety and communication purposes, Wellington Radio, ZLW was established in 1912 and was originally located in the clock tower of the old GPO building in Featherston Street. This site was proved to be unsuitable and shortly thereafter, still in 1912, the station was moved to Tinakori Hill and has operated from there ever since. ver the years ZLW has maintained radio communication with shipping and aircraft, island and lighthouse communities and also operated New Zealand's international telegram and telephone circuits to Australia and the United States. Currently the station maintains a 24 hours listening watches on three radiotelephone channels for ships and one 24 hour listening watch on a radiotelegraph.

Back to top

This interview was made in about 1980

THE FIRST QUALIFIED WOMEN RADIO OPERATOR IN NEW ZEALAND

Marie Hurst

Marie Hirst has always had a hankering after a challenge and says she was never one to follow the leader, so it does not come as much of a surprise that next month she will graduate as the first qualified woman radio operator.

She will be qualified to transmit telegrams, weather reports, and gale warnings to ships, to operate and monitor the international morse code circuit, and to operate the radio–telephone for the New Zealand Post Office.

If that seems a rather unusual occupation for a girl Marie says she is quite at home with all the knobs and dials and finds it the most challenging job she has ever done.

Picture 9: Marie Hirst Operating

After leaving school Marie, who is 21, worked in the telegraph office of the Post Office for a year and a half before deciding to train to be a radio operator.

Course

The course, conducted by the Post Office, involves two examinations, one on telegraph and one on radio operating. To qualify students have to be able to send and receive up to 25 words a minute in morse. However,through her experience in the telegraph office Marie had already sat and passed her telegraph examination so she will be qualifying ahead of some of her other classmates, one of them is another girl.

Although Marie’s class is predominatly male – she says she has had a few problems.

“The guys are really great, well mannered and pleasant to work with and we have lots of fun” She says, and adds that when the course is finished and everyone heads in different directions there are plans for a big get–together on the West Coast.

“The two male instructors,” she says,“have been specially helpful and with them around there’s never a dull monent.”

The men on the course have no doubt found it quite an experience to have a woman in their midst, and because Marie is about to graduate from the Academy of Elegance, a school of grooming and deportment, they would probably also appreciate a touch of glamour.

More Women Should Be Involved

Marie thinks more women should follow up a career in radio operating, because although if it involves shift work and some strange hours she has found it both stimulating and rewarding.

Once she is through her course Marie plans to do some further training on the job in Wellington and then see what other courses and options are open to her in her career.

Although she is rather hesitant about going to the Chathamm Islands, where they have yet to install adequate facillties for woman radio operators, Marie would love to get a job on board a luxury cruser, but that involves doing a separate course in her own time and she might not be able to fit it in for a while.

In the meantime she is really enjoying her training in a field relatively unexplored by New Zealand women.

Back to top

From the “Dominion” for 22 July 1997

TOWERING PIONEERS OF THE AIRWAVES

In the battle to protect Wellington’s green belt from subdivision, the history of what was once a vital telecommunications site has been recalled. Alan Samson reports

George Askey, 88, remembers being threatened with shooting should he forget his password as he finished the wartime “dog watch” shift on Mt Etako. John Gray, 68, recalls the l 962 laying of the telephone cable from New Zealand to Australia “which killed us”. Peter Moore 52, has memories of two young Pacific Island students who spent their lunch hours racing each other to the top of the 45–metre towers. To generations of Wellington residents, Mt Etako – the high patch of land behind the Botanic Gardens that can be clearly seen below Tinakori Rd as far as Parliament and the harbour – is a place of high towers and stark silhouettes. To the three ex–post Office technicians, whose years servicing the diverse transmission and receiving installations on the hill spanned the 1940s to the end of the 1980s, the memories are of pioneering days linking New Zealand with the rest of the world. Memories like the setting up of the first trans–Tasman telephone call – a brief conversation on November 25, 1930, between Native Affairs Minister Sir Apirana Ngata and acting Australian Prime Minister James Fenton. Or the first SOS from the stricken Wahine on April 10, l968, when 51 died as the ship foundered in Wellington harbour.

The initial charge for a call to Australia, incidentally, was £1 a minute (about $3). The New Zealand–United Kingdom telephone link was opened on July 23, 193l. The rate was £6 15 shillings for a three–minute call – lowered in 1935 to £5 2shillings. The old technicians recall that it was necessary to book calls that could be transmitted only between 2am and 6am. But a more significant date for Tinakori might have been l936, when it became possible to also call the Awatea, the Union Steamship Company’s prestige passenger liner, and to have calls overseas “scrambled” by speech inverters for secrecy. The bulk of Tinakori’s work has always been with marine communications, with the transmission from the hill and the receiving – at least after 1946 – from Makara. From Tinakori emanated the links with big ships and small and the weather reports that advised them. In the industry they talk of the “famous emergency frequency” – 500 kilobytes – which required a round–the–clock listening by groups of men sitting in the control room with headphones. Over the years the hill has been a bustling place, at its peak six towers were humming with maritime radio spilling into telepaging (one of the first New Zealand sites), FM broadcasting, mobile phones and some land mobile services (for taxis and carriers).

Old technicians and engineers aside, few today would appreciate the history of the diverse installations. Attempts to set up a special museum, like the Wahine, have so far foundered. Prod the technicians, however, and you get abundant stories. In the early days the equipment housed spark transmitters, instead of valves, using electrical arcs across coils like an old Model Ford T transmission. Today the six radio high–frequency towers have become just one. “It was the cable (to Australia and, later the United States) that killed us,” Mr Gray says glumly. “It was the start of really good communications. Then the satellites” Describing himself as “old hat” Mr Gray is happy to reminisce about the days when a lot of keen amateurs worked with ingenuity and invention. “You couldn’t buy stuff so you had to make it,” he says. “When we built the first mobile gear, we started with old bits from wrecked aeroplanes. We were a bunch of enthusiasts.

We loved our job’s”. Mr Askey provides even older memories. “During the war we had problems at night on the dogwatch, we had to have a password. There were armed sentries there and you could get shot.” Mr Askey recalls secret war messages being relayed between New Zealand, Australia and the United States, army and navy. The air force communiqués, he says, were relayed from Makara. All messages were in Morse, the diplomatic ones encoded. And the Morse was not this modern dots and dashes stuff, but marks and spaces. He also recalls desperate midnight sprints, tripping and falling, down a track into Northland to catch the last tram home. Today? Maritime services are now tinder the control of private company BCL, based at Avalon, and with a remote–control station in Taupo. With most sophisticated communications now in the realm of satellites, Tinakori’s role has been reduced to mainly mobile phones and paging transmitters. It is also home for cellular transmission, there’s a radio tower, and a microwave repeater which is part of a South Island link for television signals. There’s also some “point to point” equipment, to extend the capacity of landline links to remote islands. But, as satellites and computers revolutionise the nature of our communications, there is no longer need for technicians to live on-site. Or for keen enthusiasts.

Earlier this month, Wellington Central MP Richard Prebble and the Wellington City Council signalled a battle to protect Tinakori Hill and other parts of the city’s “green belt” from subdivision. The battle in relation to Tinakori Hill, was announced to stymie reported Telecom plans to sell off 24.3 hectares. Telecom has since responded that it is happy to give 15 hectares of the land back to the council, keeping just seven for its remaining installations. This leaves two and a bit hectares – long occupied by houses and flats, originally used by technicians and maintenance men but now rented – that Telecom wants to have rezoned residential.

Spokeswoman Linda sanders says Telecom is not interested in profiteering but is genuinely concerned for the future of the residences that have become an established feature. In response, the council’s town belt curator, Roger Still, says that the present goodwill cannot be taken as being set in stone. But, he says, the council’s real fight is with the Crown which “erred” in allowing the belt to be eroded in the first place. Both sides are agreed that the land with the solitary radio tower should have free public access. For Mr Askey, Mr Gray and Mr Moore, whatever the outcome, there are memories tinged with sadness. Today’s telecommunications, while more efficient than any of them could ever have dreamed possible, just ain’t what they used to be.

Picture 10: Visitors Hill are silhouetted among the towers

In Picture 10 visitors to the top of Tinakori Hill are silhouetted among the towers which are becoming relics of a bygone era of telecommunications. With most sophisticated communications now in the realm of satellites, Tinakori’s role has been reduced to mainly mobile phones and paging transmitters

Back to top

From Reg Motion ZL2LX December 2006

WHEN THE ANTENNA CAME THROUGH THE ROOF

NOTE: This text refers to Pictures 11, 12 and 13 below

ZLW was quite an interesting (sometimes exasperating place). I only spent a few days there just before I was sent to Fiji in 1940 and it rained and blew all the time. I have some early photos of the transmitting station which I can loan you if you wish.

One of the most interesting stories I found on ZLW was in an old file at Radio Section (long ago destroyed). In the early 1920s the “powers that be” decided to replace the then wooden masts with towers. These they imported from Milliken Co in USA but failed to notice that the maximum wind velocity these towers were designed for was 90 mph (144 kph). The towers were duly erected and stood for a little while then some keeled over in a Wellington gale (panic stations when the second tower collapsed).

A hurried conference and it was decided to guy the remaining towers using guys with heavy springs in them to keep the guys taut. The inevitable happened – these towers just buckled at the lower section and sat down still upright but much shorter.

Sanity prevailed at that point and then MOW was asked to design suitable towers which they did using no steel section less than 0.25 inches in thickness. The Milliken towers used 0.125 steel and their cross braces actually bent when a rigger stood in the middle of them – undoubtedly they were OK for amateurs in the less windy States of good old USA. Interestingly the MOW towers were still standing when ZLW was decommissioned.

The press of the day had some caustic articles on these goings–on – might be worth while looking them up for any story. About 1921/22 as I remember. Refer to previous article–it happened in 1926

Thank you Reg – ZL2NN Added 24 December 2006

NOTE: This text refers to Pictures 11, 12 and 13 below

Picture 11: Taken before the antenna crash shown in the pictures below

Picture 12: The transmitter building copped the lot. The antenna crashed down across the building roof. The noise of the crash was heard in Wellington city

Picture 13: Cause of the antenna crash shown in Picture 12 above. It was caused by a bolt shearing in a 1926 Wellington storm

Back to top